You Did What with Your Van?

Barn Swallow

This Barn Swallow left its wintering grounds in South America in February or March. It arrived at Ottowa National Wildlife Refuge in Ohio, probably in early May, where my migratory path intersected with its path.

Whether this little guy is staying in Ohio or moving even further north is unknown to me, but there it was, posing so beautifully on a railing as I rounded a corner.

As a long-distance migrator, Barn Swallows travel approximately 14,000 miles annually between winter and summer grounds, facing unimaginable challenges with weather, habitat loss, city lights, windows, and predators.

My route had its own challenges but, thankfully, far less than the Barn Swallow's, or any migratory bird for that matter.

On May 13, I pointed my van west and embarked on a personal and professional journey to explore migratory bird pathways, learn about them, write, draw, and to see as many bird species as possible.

Red-winged Blackbird

Here is my trip, NH to AK, by the numbers:

4.5 weeks

All 4 flyways

15 states, 2 provinces

8 national wildlife refuges

4 wildlife areas

1 national park

2 provincial parks

7408+ miles

122 species of birds

19 lifers

To say this was an epic undertaking is an understatement.

As I sit here with this experience behind me, my mind goes to connecting bird species to specific habitats through first-hand observation. I come back to the underlying purpose of this trip.

First, being present with the birds in their habitat; hearing them vocalize, watching them soar or flit about; that direct connection triggers a sense of awe in a deep impactful way irreplaceable by books.

Second, there is incredible value in spending time alone to improve field skills. All the group walks and talks and all the books are necessary and helpful resources. Getting out there to observe alone builds one’s confidence while solidifying a knowledge base.

American Robin

Magnolia Warbler

My official list of species reflects birds I had very good looks at as well as species heard. I counted everything, from the most common like the American Robin pictured above on the left, to the Magnolia Warbler on the right.

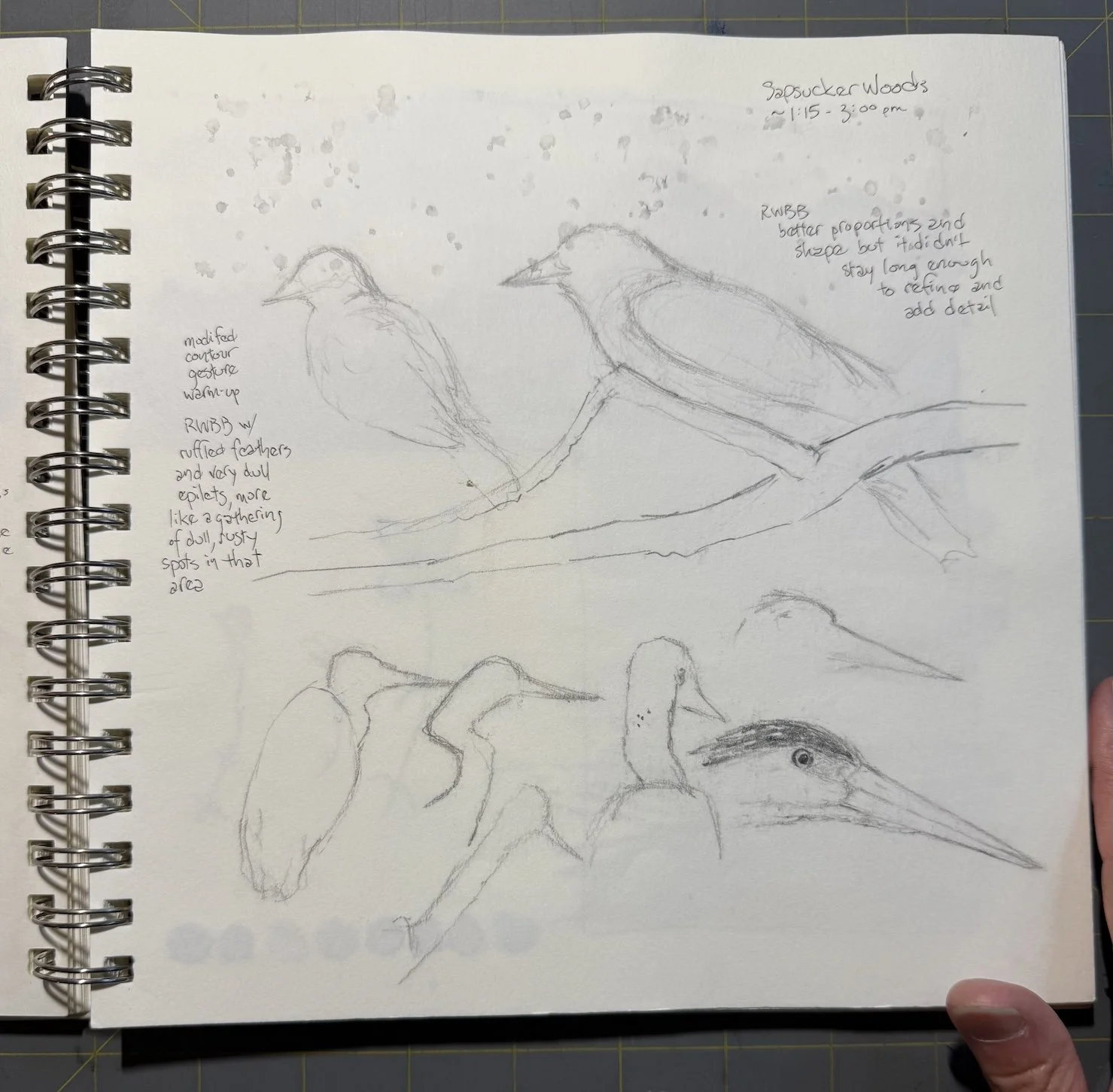

Sketching at Sapsucker Woods, NY

Trekking began in my home state of New Hampshire. The logistics of the trip were complicated and I could not plan for a day of birding before heading out, so my one stop under the Atlantic Flyway was Sapsucker Woods in western New York state.

You might know it. Sapsucker Woods is connected to the world-renowned Cornell Lab of Ornithology. If you use the Merlin app or eBird, you have a relationship with Cornell.

I didn't accrue any lifers at this first stop but there were two species I kept hearing that I could not visually pin down: the Northern Waterthrush and Great Crested Flycatcher.

Wandering the forested trails that criss-cross a meandering body of water, searching longer than I should have, they both managed to elude me. I had to stop and get back to my van. Alas, it would not be the last time on this trip a bird taunts me with its song and hiding skills.

From there, I continued west and a little south to the Mississippi Flyway. Under the Mississippi Flyway I spent a full day in three locations: Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge and Magee Marsh Wildlife Area in Ohio, and Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge in Iowa.

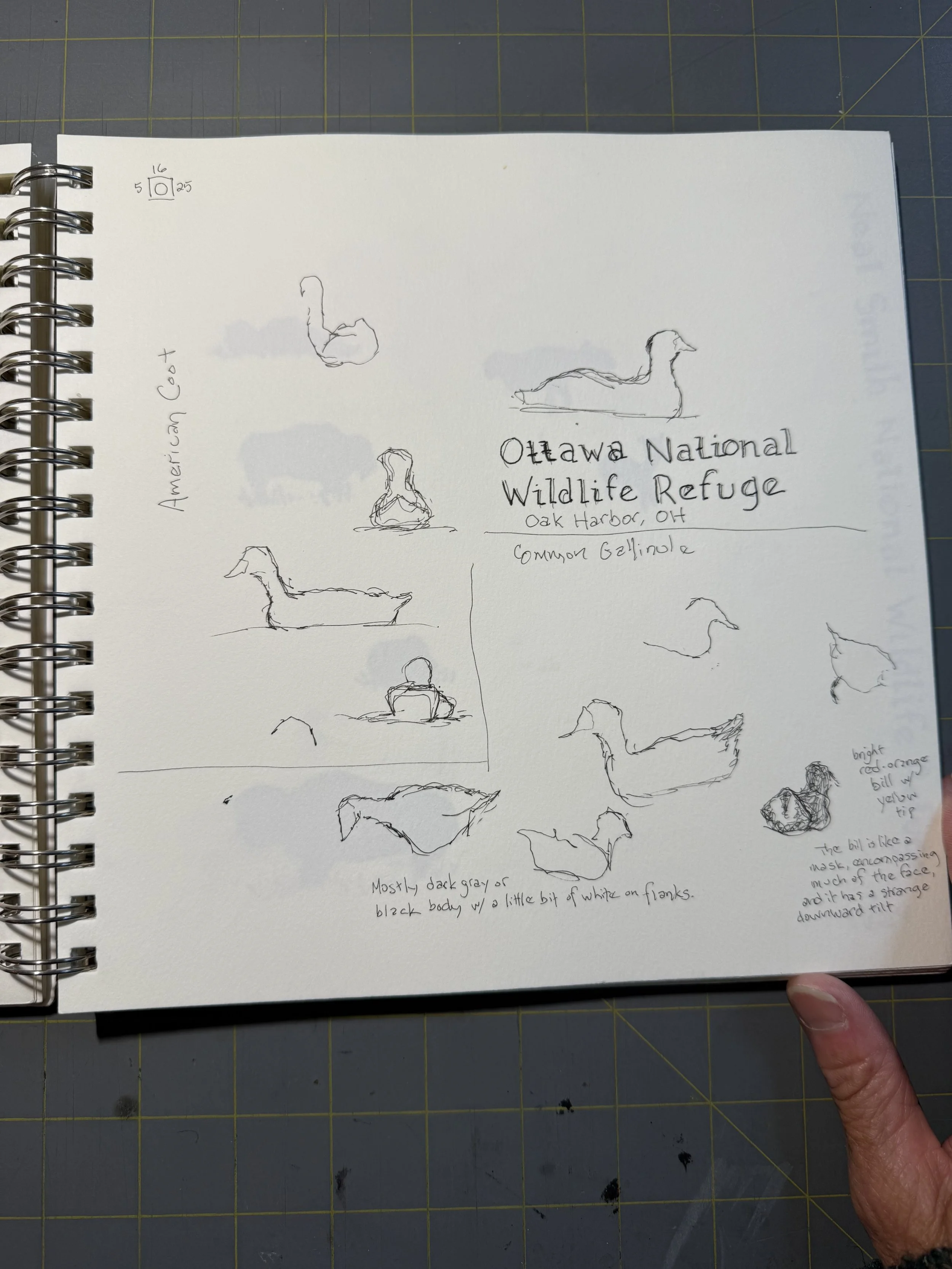

Observing and sketching at Ottowa NWR, OH

American Coot and Common Gallinule

Sitting between flat farmland and Lake Erie, the Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge and associated wildlife areas are made up of a number of different habitats from sandy beach with a wooded edge to thin forest surrounded by lots of water, to canals lined with grasses and shrubs.

I arrived as peak warbler migration was just starting to wane! There were thousands and thousands of warblers, sparrows, and other birds passing through or staying to nest!

This is where I picked up the first four lifers: Bay-breasted Warbler, Prothonotary Warbler, Black-billed Cuckoo, and a species I never knew existed, the Common Gallinule (seen on the journal page above).

Connecting species to habitat, the warblers and cuckoo were spotted in thin forested spaces abutting Lake Erie. The Common Gallinules were in a water canal.

Neal Smith NWR, IA

At the western edge of the Mississippi Flyway, in the prairie grasslands of Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge in Iowa, I had a half-day to seek, listen, and sketch. Completely alone here early in the morning, it was quiet except for the wind and the birds.

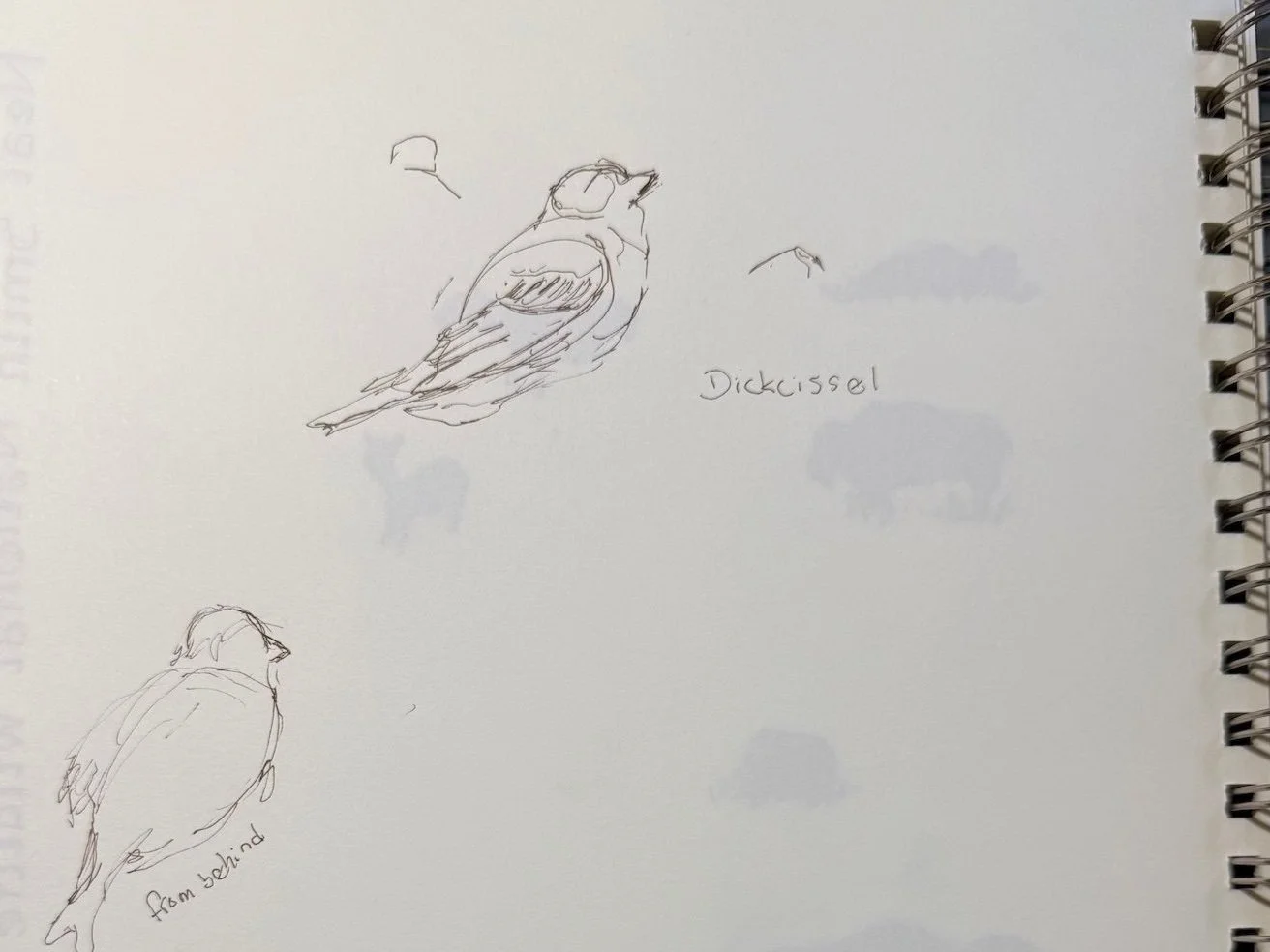

The fifth lifer of this trip is the Dickcissel, currently considered a member of the Cardinalidae family. This species has confounded genetic scientists for quite some time.

Dickcissel

Regardless of the genetics, what a beautiful, colorful bird! Black, white, gray, yellow, and rust feathers cover its body, keeping it well hidden in a tall grass habitat.

Arriving at the refuge early proved rewarding (no one else on site means no sonic distraction; my ears were taking in the many bird songs). However, the birds were incredibly busy inside the tall grass, not revealing themselves to me.

Is this their routine, I wondered, to stay low in the early morning hours, and pop up to the top of grasses and shrubs with the sun’s rising?

An hour or so passed and I got my scope on one of them. It perched in place long enough for me to work up its general shape, proportions, and angle but not long enough to capture a variety of poses. And suddenly, it was time to move on.

This experience led to the first lesson of the trip: schedule more time in the field at each location.

Two days later, at the eastern edge of the Pacific Flyway, I reached Jackson, WY to attend the inaugural Jackson Hole Birding Festival, the pinnacle stop on this journey. After eight days of traveling solo, I can honestly say there was a sense of joy being with people again!

Five full days at the bird festival in Jackson proved immensely educational. The work in the field, observing and exploring in a new habitat; observing and id'ing as many birds as possible; all expanding my knowledge base.

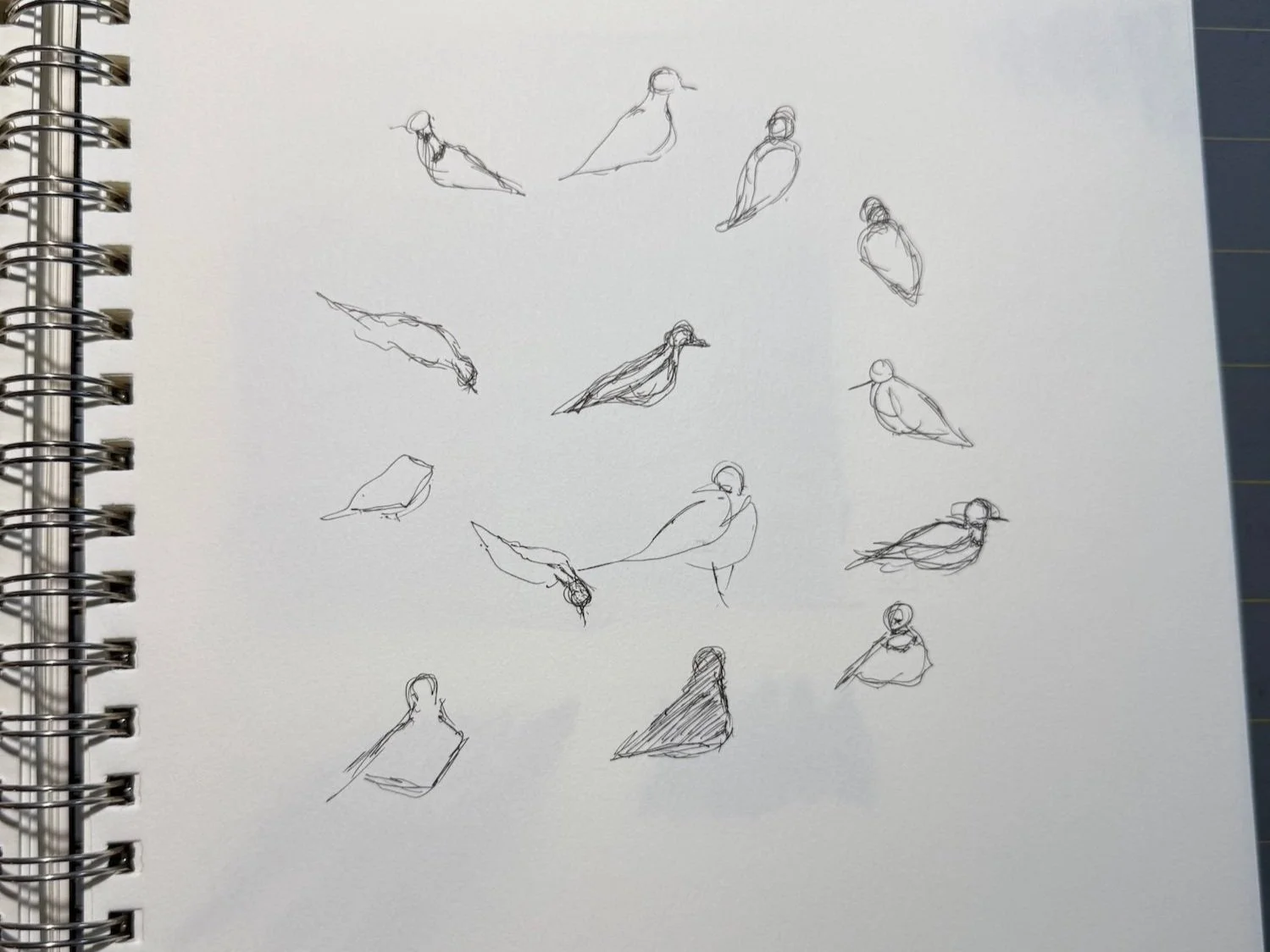

Sketching along the Snake River in Grand Teton National Park

But also, meeting interesting people, making connections, listening to stories from incredible speakers, and talking to others about the work I am doing on the road satiated and saturated my brain.

AND two of my paintings were included in the festival's art show amongst a diverse collection of bird-related artworks. So cool.

The five days resulted in eight pages of sketches, like these Long-billed Curlews, at a variety of habitats in Jackson, from expansive fields to mountains to rivers and lakes.

Also, it was here that I saw the next two lifers, a Bullock's Oriole, who flew from Mexico to nest in the open woods below the Tetons, and the Brewer's Sparrow, a habitat specialist of the western sagebrush landscape.

It was in a grassy body of water on the National Elk Refuge is where I met the next bird to taunt me with it's loud and proud song and superior hiding skills, ... the Sora.

Van sketching

Never saw it, despite several hours of jerking in its direction every time it sang, convinced I'd get my eyes on it. My patience ran out and I needed to move on. Had I spied it, the Sora would have been another lifer.

All told, in the five days spent in Jackson, 37 species were visually identified.

I was sad to leave Jackson but I still had a ways to go and a special person to meet down the road.

The next stop was the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge in northern UT. It did not disappoint.

White-faced Ibis

It was there that I got the next lifer: Cave Swallow. I stood amongst hundreds of them as they swirled and soared around me, lifting my spirit into their collective acrobatic flight. This bird completed my list of swallows in North America!

There was a lot of walking and driving, but I had a good, long session along the Bear River where I watched and sketched a White-faced Ibis.

I was generating sketches that felt more developed; ones that held my particular creative response to what I was observing.

Having time to be in one spot plus a "cooperative" bird made all the difference. There's something on this page - a beginning - that I want to explore more going forward.

All this led to the second thing I learned: "warming-up" my proficiency in field sketching live birds, like training for a race, is a necessity before embarking on a trip like this.

A full day of birding on my own under bright sun and pretty intense heat added 15 additional species to the list and powered down my body battery. I slept well that night.

I didn't know it at the time, but in UT I was sleeping under the Wasatch mountain range, known for about a dozen summits rising above 10,000’. Willard Peak, the base of which I was closest to, rises to 9,743’. That's pretty cool.

A two-day break in Idaho provided good nutrition for the body and soul. I reunited with my husband, visited with friends who cooked marvelous meals, and explored Deer Flat National Wildlife Refuge.

A third bird slipped through my fingers here – and would prove impossible to see for the rest of the trip – Bewick's Wren. But I found my 9th lifer, the Black-chinned Hummingbird!

As we moved southwest from Boise, we found amazing birding stops along back roads in Oregon. A pull-off on Rt 20. Klamath Marsh NWR on rte 676. Upper Klamath Lake on Rt 97. Easy access for travel and birding.

We even stopped to smell the bark of one of my favorite trees, Ponderosa Pine. The sweet vanilla aroma fills the air on warm windless days.

Ponderosa Pine

Petroglyph Point

The jaw-dropping awe continued as we hit a number of places in the Klamath Basin NWR Complex: Tule Lake NWR, Lower Klamath NWR, and Petroglyph Point, all in California along the Oregon border.

In search of birds and whatever else we could spot, Petroglyph Point was an unexpected and very cool cliff habitat that supports a handful of bird species throughout the year. Due to a massive outbreak of midges anywhere there was water, this was the only place I sketched that day.

The Klamath ecosystem, straddling southwestern OR and northwestern CA, is an incredibly rich ecosystem of diverse habitats supporting a wide variety of flora and fauna: 3500 vascular plants (280n endemic), 36 different conifers (18 endemic), 400 wildlife species (490 avian).

Astonishing! Not only that, the region has a rich geologic, natural, and cultural history. It warrants more exploration someday.

Greater Klamath Ecosystem

Which leads to the third thing I learned: develop a deeper appreciation for an ecosystem while in it. (Knowing leads to caring. Caring leads to stewardship. Stewardship leads to conservation. A guiding principle in my work.)

This ecosystem produced two more lifers for my list. The Black-headed Grosbeak and Black-necked Stilt, the latter which I'd seen at the Monterey Bay Aquarium a number of times in the past. Seeing it in its habitat is what counts as a lifer for me.

Killdeer

We made a direct trajectory for Olema, CA, having amazing views of Mt. Shasta on the way. Not so straight, though. The van chugged over the beautiful but steep and windy Coastal Ranges with dignity, if not slowly. We were all a bit road-weary.

That evening in Olema we birded around our campsite. Two more lifers... #12, California Towhee (which didn't look anything like the other towhee species I knew), and #13, California Quail, which I probably saw when I lived in California all those years ago but wasn't really paying attention to so it didn't count until now.

My time in CA was a necessary extended stop to teach my virtual courses and visit with family and friends. In between the teaching and visiting, birding happened.

Six more lifers were added to the list: Pygmy Nuthatch (so cute!); Western Gull (a mighty big gull); Western Flycatcher (can't mistake that flycatcher shape); Hutton's Vireo (this one I could mistake for a number of other birds); Wrentit (with its somewhat dull expression); and Bushtit (with its rather serious expression).

It wasn't entirely about the birds. If an opportunity to observe and sketch a different kind of animal, then I did! Elephant seals at Point Reyes National Seashore!

Elephant Seals

The Bewick's Wren continued to hide from me in California, its song reminiscent of a Song Sparrow's. I had fun watching and sketching a Killdeer while walking along the beach at Asilomar on Monterey Bay.

Latest addition to my Ten Littles project

With a fresh loaf of bakery sourdough and a bunch of other provisions, we left CA for the long haul back to Alaska, but not without some birds along the way. Like Jackson, WY, we hated leaving CA.

Every day was a long drive, but we made sure to make stops if a roadside spot or sign looked promising to see birds. This is how we found Delevan National Wildlife Refuge in California’s northern central valley.

The birding on this leg of the trip was always spontaneous and usually quick, so I switched to working up a few of my little paintings for the Ten Littles project.

As we moved north through stunning landscapes in the Canadian provinces of British Columbia and Yukon, the daylight lasted longer and longer.

This days-long stretch follows a valley between most of the tallest mountains in North America: the Coastal Mountains to the west and the Rockies to the east. A new summit greets you at every turn in the road.

Despite the endless wildfire smoke we took in the grand views, and birded right up until the last night while camping at a rest stop just over the Canadian border into Alaska.

Sunrise at Green Lake BC Canada

Leading to the final and most important thing I learned on this journey. I can – and should – do this project.

The challenges faced – dangerous cross-winds while driving (still feeling the effects), a shortage of calories in my diet (more protein, please!), a dead battery (twice) – all are navigable.

This is a grand opportunity, something I've been working towards for so many years, with the path wide open and a big sign that says "This Way". To not go would be regretful.

All this leads to a big decision. My art and writing project to observe birds on migration will officially begin in the spring of 2027.

There are many more things I learned on this trip, things that will guide me to the next phase. Over the next 18 months I'll share those insights, as well as the successes and challenges along the way.

Maybe what I learn can help you in your own endeavors.

Stay with me folks. This is going to be the ride of a lifetime!